Test Double - dummy, mocks, stubs, fake objects, spies. All the gang in one place

Have you heard about stunts doubles in action films? You know? Those people whose job is to receive punches, kicks, and pretty much any type of damage to sell an action scene convincingly, without exposing the actors and actresses to any danger.

In movies, stunt doubles are hired due to their preparation for action scenes. Furthermore, they allow the movie's production to not depend on the actor to do those dangerous scenes, exposing himself to injuries that could affect the film deadlines and incur on extra expenses.

Hollywood actors and their stunts (Keanu Reeves, Andrew Garfield, Will Smith, and Jackie Chan 🤣).

Hollywood actors and their stunts (Keanu Reeves, Andrew Garfield, Will Smith, and Jackie Chan 🤣).

Table of contents

- What are Test Doubles

- Types of Test Doubles

- Mocks aren't stubs

- Practice is different from the Theory

- Practical situations when Test Doubles could help

- Prepare your nose for the smells

- Final thoughts

What are Test Doubles?

Test Doubles, is a term coined by Gerard Meszaros (Meszaros, 2007) they are the equivalent of stunt doubles, but in testing. The context is different, but the idea remains.

💡 Replace the original object with a copy that looks the "same" but behaves differently

Unlike stunt doubles who replace the original actor in some scenes, we don't replace our original code under test; we replace its dependencies. More specifically, we are breaking a real dependency to use our Test Double instead.

Why do we want to replace the dependencies of the code under test?

Michael Feathers explains it well in his book called "Working effectively with legacy code" (totally recommended).

There are two main reasons to break dependencies in favor of testing: Sensing and Separation (Feathers, 2004, p21-22)

- Sensing. We want to see what is happening inside the code. What values are computed, and what calls are made.

- Separation. We want to separate the code from its dependencies because we can't even start testing due to multiple requisites to instantiate dependencies or because they take too long to be ready.

Types of Test Doubles

There are multiple Test Doubles, created for different situations. In this section, we'll learn them, their applications, and their characteristics.

Note: From now on, we'll follow the testing jargon, referring to the "code under test" which is also called "System Under Test" as SUT and to its dependencies as collaborators.

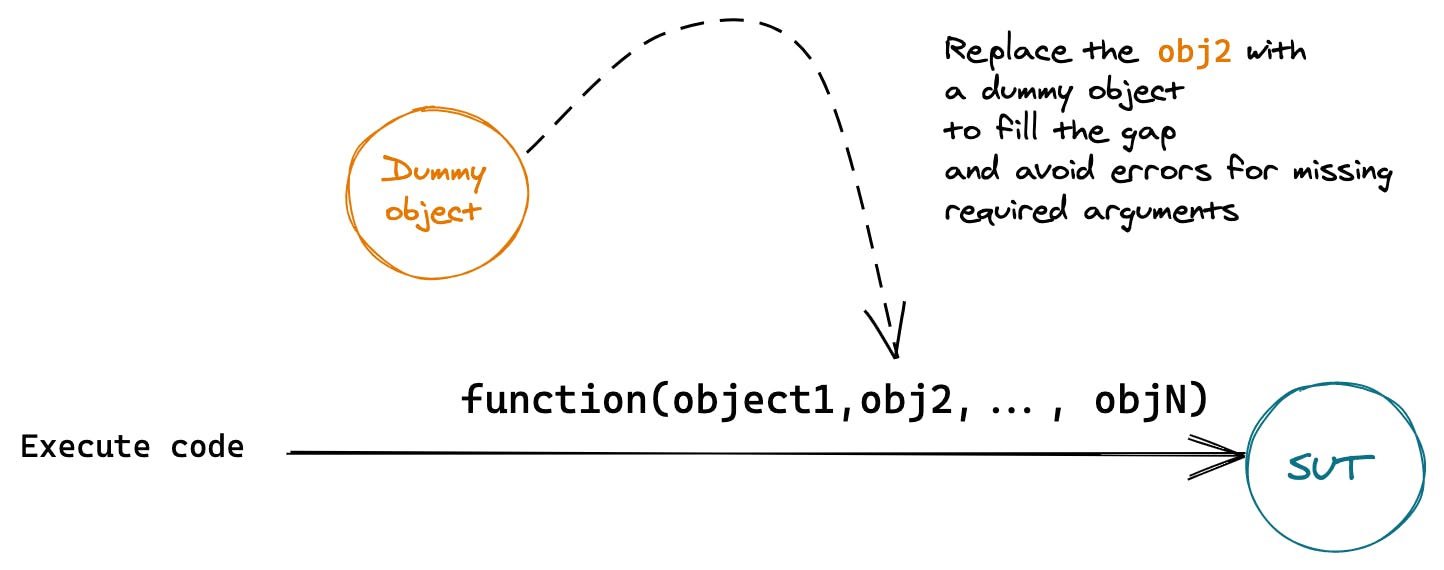

Dummy objects

Perhaps you've encountered functions or methods that require more arguments than we actually need for testing a specific logic path during a test, and to avoid errors when calling the function, we fill the spaces with null or empty objects. Those objects that we passed down to the function are called dummy objects.

Dummy objects are passed around but never actually used in the code; their only purpose is to prevent errors when we don't respect the function's signature.

We can use any type of value like numbers, strings, and so on, is not necessary to always use null objects;

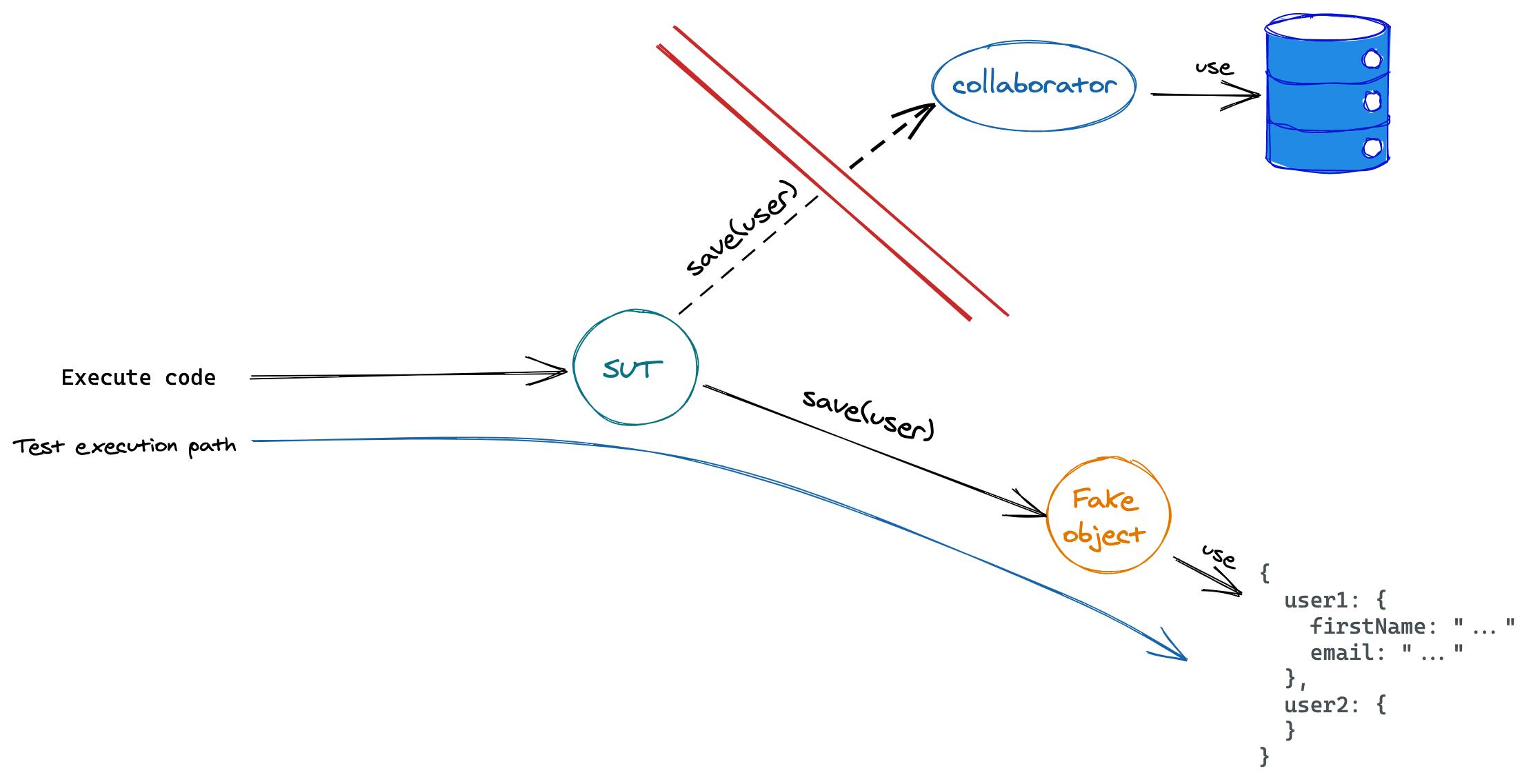

Fake objects

Fake objects are usually objects whose implementation is written by us, just like our code under test. They are used to replace the original implementation because it's too slow or it cannot be called during the test.

For example, on some tests, devs write their own "persistence layer" to save data and use a hash map as an In-memory database instead of calling the actual database due to is much slower and will slow down the tests.

Fake objects are often used in pseudo-integration tests or to replicate effects that could be too hard to do with the real collaborators

The downside is that we have to maintain those objects and write tests specifically for their functionalities.

Stubs

Stubs are like a fake object but with no more than one line of code implemented: A return statement.

function stub(value) {

return value;

}

They are used to return constant values, and _most of the times, they don't return anything

function theMostSimpleStub() {

}

function theMostSimpleAsyncStub() {

return Promise.resolve();

}

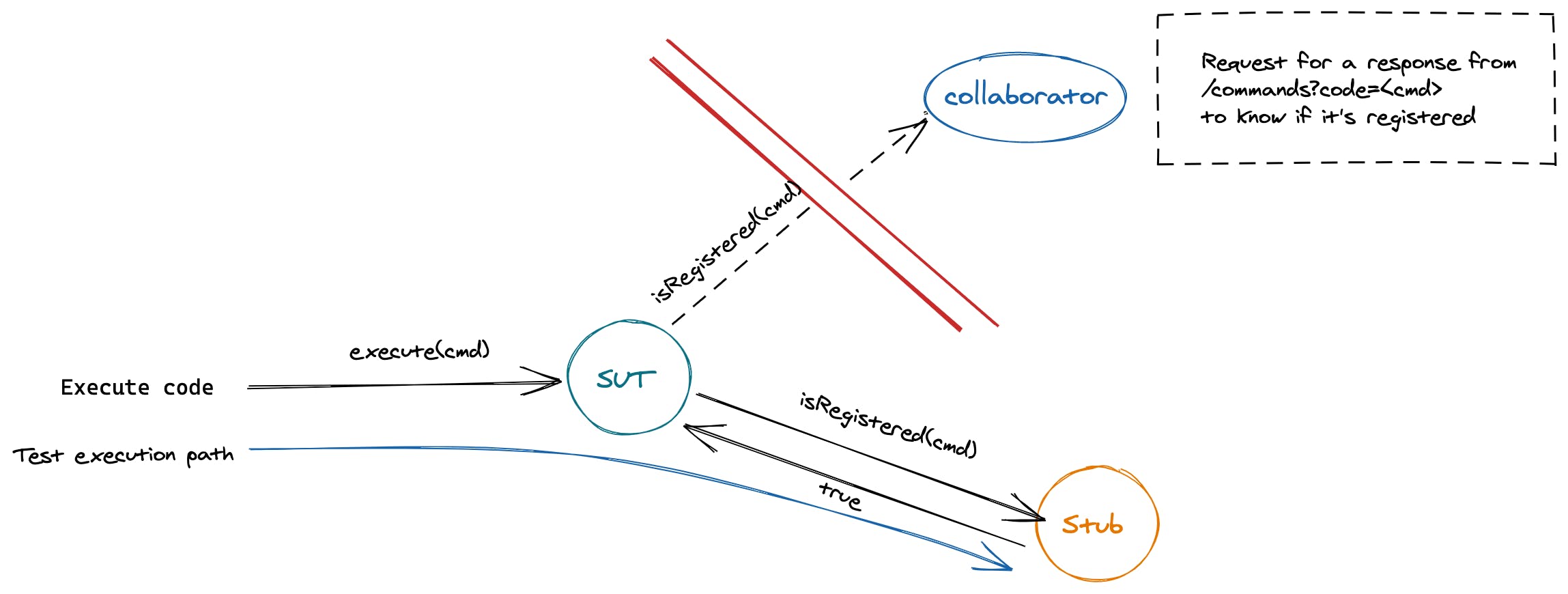

Its main use is to direct code's execution and contribute to verify state changes in the SUT through the values provided by itself. Stubs guide the code execution path, providing the necessary values to enter conditionals (if and switch statements) or to continue immediately when the code reaches a blocking point, like waiting for asynchronous code to finish its execution.

Spies

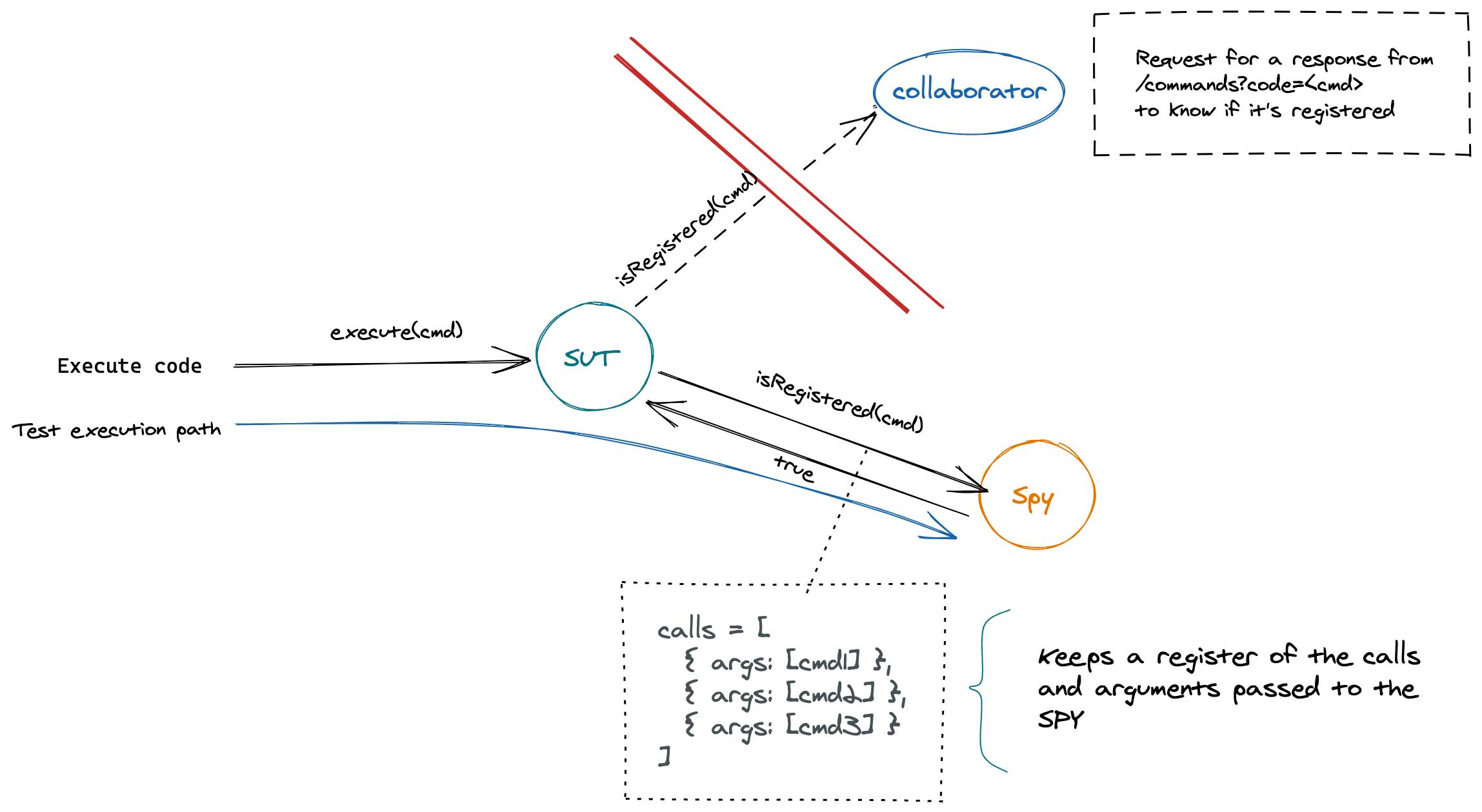

Spies' purpose is to record the calls we made to a function or method. They are used to sense the behavior under test, to know if the functions are executed in the correct order and with the expected arguments.

They are stubs augmented, thereby don't execute the real implementation, and instead, they can return predefined values, but additionally, they act as proxies to record arguments.

Spies perform the same verification as mocks but with a different syntax. In both cases, we check the behavior rather than verifying if the resulting state after executing the SUT has changed.

There are two types of spies: Some are anonymous functions, while others wrap existing methods on collaborators

Mocks

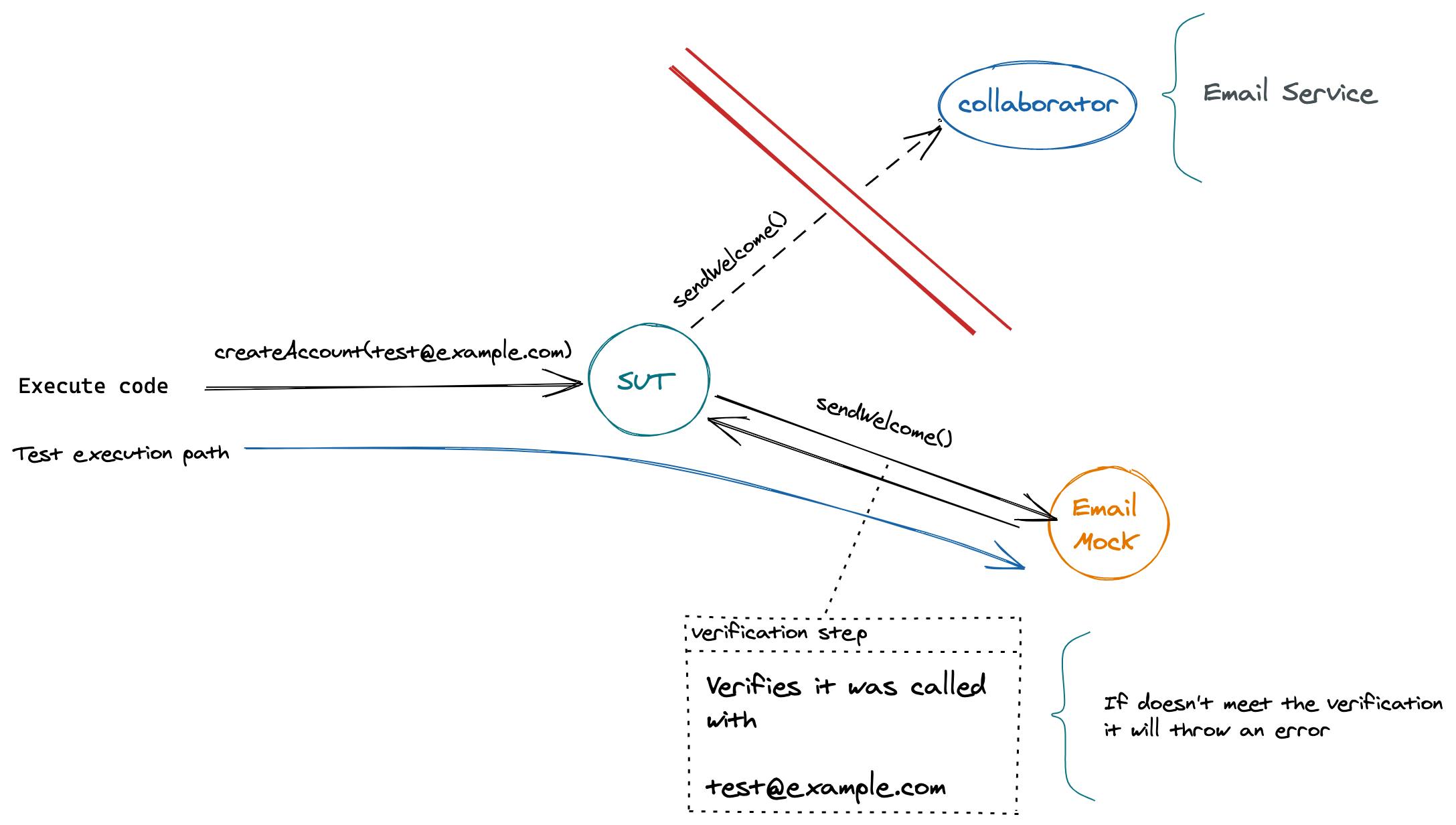

Mocks are objects pre-programmed with responses but different from Stubs because they also contain expectations that work as contracts of the calls they are expected to receive. They have a verification phase where all the calls made to the mock are compared to seek if they match against the calls and arguments expected. In case of any inconsistency, mocks can throw an exception when they receive an unexpected call.

Mocks aren't stubs

Developers tend to relate the word "mock" to the general action of replacing real objects with special objects that mimic the structure of the original ones. As we saw before, we can use many special objects to achieve that, and not necessarily need to be mock objects; we can do the same with stubs. Because of that, sometimes devs, when talking about "mocks," are referring to stubs or spies without knowing it.

Mocks and stubs have similarities but also differences. The main one is that mocks set expectations for their future calls. That distinction creates a whole different way of doing testing.

When we use mocks, our goal is to test the code and know how it was executed; what paths it took, which arguments its mocked dependencies received, how many times those functions were called, and sometimes, even in what order were executed. By using mocks, we are doing behavior verification.

In contrast, with stubs, we fake values and method responses to drive the system under tests (SUT) execution, and at the end of the test, we check if the final state was the expected. By using stubs, we perform a state verification.

Mocks aren't the equivalent of stubs. They are similar but mocks enable a different style of testing.

Behavior verification, using mocks, changes the common anatomy of functional tests, altering how the tests are structured by adding new segments to set the mock's expectations and also requesting its expectations verification.

Nevertheless, we can also perform behavior verification without using mocks, but spies instead. With them, we can fake the implementation, set expectations to check the code to behave as we want, and all of that without changing the test structure because with spies, the verifications are writing at the end of the tests as we usually do.

So, you may wonder, why use mocks over spies then? Or why follow a behavior verification over verifying the state? I suppose it is a simple preference. In software development, we can do things in many different ways. Some devs prefer using mocks and other spies to do behavior verification. Others avoid faking dependencies as much they can and check the end state of each test.

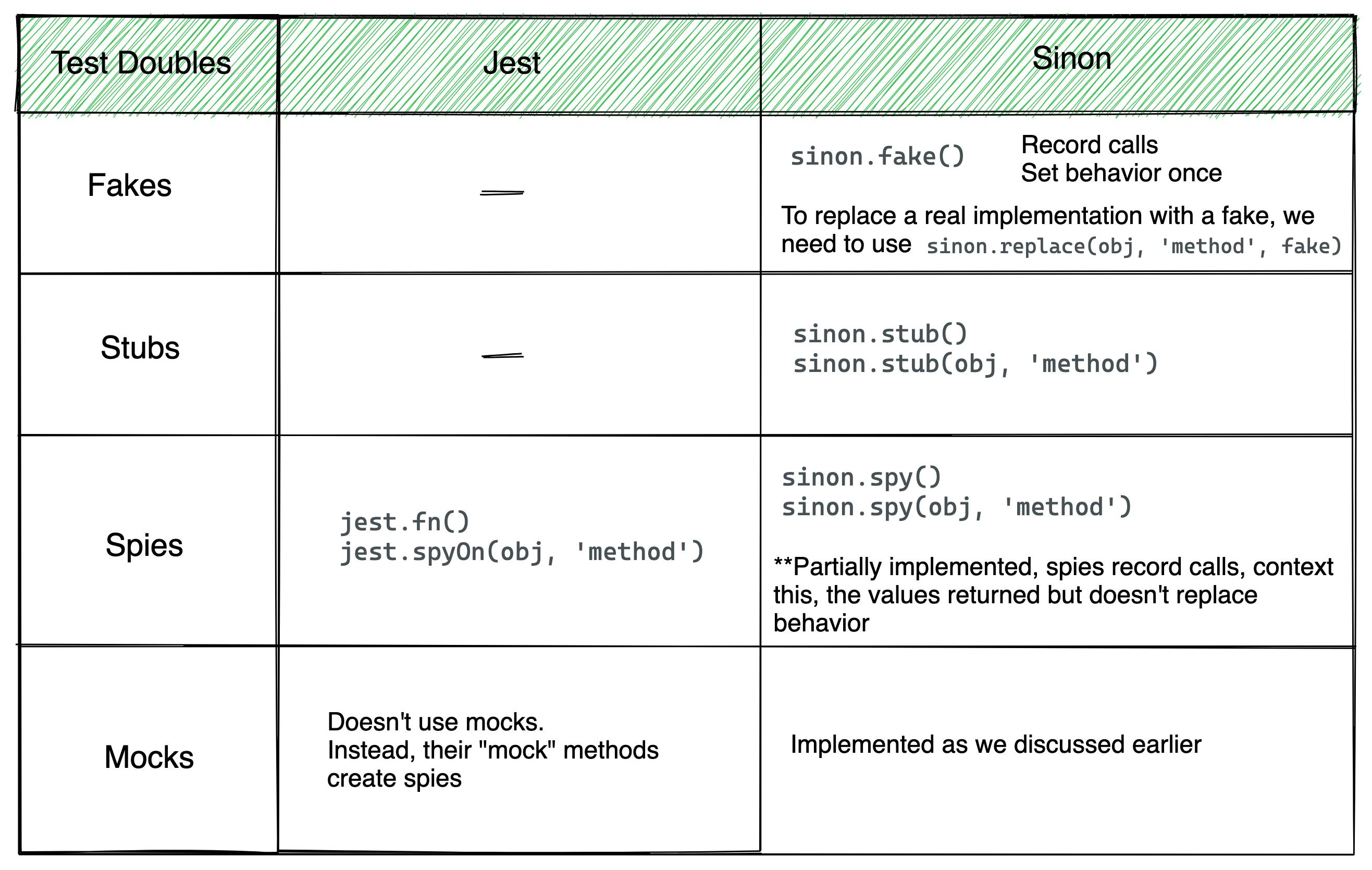

Practice is different from the Theory

Although we have different Test Doubles defined, with their specific uses. Testing libraries difficult the task of identifying each one them, the line is blurred due to the lack of standardization regarding Test Doubles definition. In some libraries, multiple Test Doubles are hidden behind a single public utility function or not implemented at all.

Comparing Jest and Sinon

Dummy objects weren't included in the comparison because they are the easiest Test Double to create, and we don't require a library for that.

As you can see, in practice, each testing library uses its own definition of Test Doubles.

Practical situations when Test Doubles could help

- Test an error hard to trigger (e.g., memory overflow)

- File management

- Caching

- Third-party system integrations (e.g., email, databases, APIs)

- Fake services to test functionalities in environments where those services are disabled(e.g

cell phone sensors)

Prepare your nose for the smells

Now you know what are Test Doubles, but I can't let you go without telling you the most important thing.

Test Doubles are a code smell!!

A code smell is not necessarily bad, but it definitely must catch our attention when reviewing the code. But why is that?

Let's see their benefits, with Test doubles we can:

- Run our tests faster

- Isolate our coupled code

- Corroborate logic by verifying Test Doubles calls while executing the SUT

Unfortunately, they also have disadvantages. When we create stubs or mocks we are faking an implementation, if we overuse them we could end testing nothing more than Test Doubles results and not the feature we intend to build.

Here an example, let's say we want to test a function whose purpose is to capitalize a given string. The function uses internally the capitalize utility from a third-party library called lodash .

import * as _ from 'lodash';

export function capitalize(str) {

return _.capitalize(str);

}

Tell me, if we replace the _.capitalize function with a stub. Could that test tell us something useful?

-- Absolutely nothing!!

However, if we prove that the _.capitalize function is called with the same input as our function, the test might be useful but it will be coupled to the library.

In this specific example, what we want is to know if our capitalize function returns the capitalized version of a given string. We can test that directly, and by doing so we free ourselves from lodash , allowing us to replace the library without having to change the tests if we want. The tests will fail only when the feature fails.

import { capitalize } from './text-utils/capitalize';

test('capitalize function should return the capitalized version of a given string', () => {

expect(capitalize('testing is awesome')).toEqual('Testing is awesome');

});

We coupled the tests to the real implementation when we do a behavior verification using mocks or spies. If the system under test changes the calls of its collaborators, those mocks and expectations will fail, which isn't a problem when the code is used in one place, but if it's shared among multiple files, every related test will fail.

Behavior verification makes our tests brittle.

When the tests depend on how we call the SUT collaborators, it also affects refactoring. If the code change, it's more likely to break multiple tests even without changing the behavior (Refactoring doesn't change a feature behavior).

You must train your senses to know when is enough of faking dependencies and when we should use the real collaborators instead.

I can give you the last recommendation: never fake business rules, you can fake any other thing, but your core logic must remain intact. Favor testing with real collaborators when you test your core logic.

Final thoughts

Test Doubles have lots of benefits and are used by lots of developers, so it's a good use of time, learning about them. Besides their advantages, consider that they can also become a source of problems when we overuse them. Don't abuse Mocks, Spies, and Stubs

Knowing all the types of Test Doubles and their use cases can help you identify when to use them, but nevertheless, remember that testing libraries could have their own definitions. Therefore you must also learn how to implement Test Doubles using your testing library of choice.

Abusing of Test Doubles can make the tests brittle and can make refactoring a challenging task, also give a false sense of security; to avoid these problems, follow these tips:

- Use real implementations whenever you can.

- Write your software composing small pieces of code. That will restrict the need for fake dependencies.

- Use mocks and spies on external dependencies and not on core business logic.

Test doubles are required when we want to sense and separate our code during testing, a helpful characteristic on legacy code to match our test with already working behavior.

If we think about it, Test Doubles are more and more required as long as our code remains coupled, so if we focus on decomposing the code into smaller units, and we probably won't need to fake any dependency.

References

Meszaros, Gerard (2007, May 11). Chapter 11 Using Test Doubles. In Addison-Wesley; 1st edition (Ed.). xUnit Test Patterns: Refactoring Test Code

Feathers, Michael (2004, Sept 22). Chapter 3: Sensing and Separation. In Pearson (Ed.). Working Effectively with Legacy Code (p21-22).

Fowler, Martin. (2006, January 16). TestDouble. martinfowler.com/bliki/TestDouble.html

Fowler, Martin. (2007, January 02). Mocks Aren't Stubs. martinfowler.com/articles/mocksArentStubs.h..