You enter a restaurant, order the food, the minutes pass, and when you are about to leave for the long wait, the waiter arrives with your food, but it's cold or isn't what you asked for 🤦♀️

What happened? The restaurant wasn't full, the attention was friendly, but the order was wrong and delivered with a significant delay...

It was the kitchen!!

Apparently, they were too busy cooking and dispatching the orders that no one took the time to properly clean and replenish ingredients, causing a big mess with the service.

It could all have been avoided if the kitchen team had organized better to clean the tools and the place while others focused on preparing each meal.

💣 The total cost of owning a mess

As a developer, can you relate to the previous story?

If you've been coding for a while, something similar already happened to you. Customers mad because the team was taken too long to fix bugs or delivering new features, and internally everything was a mess, like in the example.

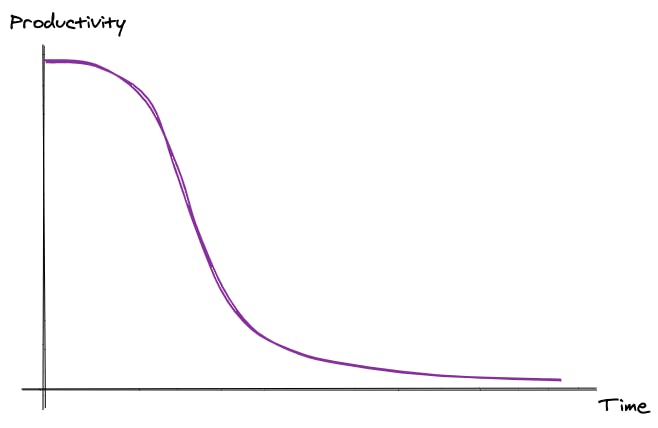

When we work on a project where the main goal is to deliver features as fast as possible or with unrealistic deadlines, developers start taking shortcuts to satisfy everyone with the results. We succumb to the pressure of managers, customers, and even colleagues. The team is too busy with unrealistic compromises, leaving no time to clean-or at least that's what we believe-, so we avoid it until one day we start noticing that we are no longer going as fast we used to.

When the team stops worrying about how complex the code is becoming, it's a matter of time until it reaches a state where it will become a complete pain to work with. Soon adding just one line of code will require an enormous effort.

Eventually, the internal problem will be reflected externally in:

- Customer feedback: due to delays, poor quality deliveries, too many errors.

- Lack of ability to respond quickly to events: Everything will require more time and effort due to how complex it is to continue working with the code.

Soon, productivity will drop, our customer complaints will rise, raising alarms within the company.

Once the project reaches that state of complexity, people will end up leaving the company, tired of working and maintaining a rotten code. In addition, the company will lose valuable knowledge and skills that took months, even years, to build.

Nobody wants to work with rotten code.

Developers will demand to drop it all ways and start over because it's no longer sustainable to work with that code. In the end, after lengthy discussions and multiple complaints, the company will acknowledge the problem and will be forced to drop the current project BUT not until the new project have all the existing features😭

Good code matters

Working with good code always matters, to you, to me, to everybody on the team, to customers and managers. Because if we can work smoothly, blazing-fast, and with less effort, it's a win-win situation for everyone.

The problem is that code has a natural tendency to get messy over time, which can be caused by many factors; some of the most common are:

- Having a system coupled to ever-changing technologies and dependencies

- Not following coding guidelines

- Taking shortcuts to fulfill customers or managers wishes

- The loss of knowledge due to the enter and leave of coworkers on the project

- Changes in the requirements

We call some of those causes accidental complexity; things just happen and affect our code. But, there is also essential complexity, which has to do with the intrinsic complexity of the problem we are trying to solve. For example, writing a personal blog is less complex than building an airline reservation system (ARS).

Nevertheless, an experienced developer can write simple, readable, easy-to-understand code no matter the complexity. Still, it's worth nothing if the rest of the team keeps adding sloppy code.

Writing good code is the responsibility of the whole team

How can we assure the code keeps clean if we are constantly adding more code?.

Simple. Making code improvement a frequent task.

🚁 Refactoring to the rescue

A good chef knows the importance of maintaining the kitchen clean and the tools sharp and ready. As developers, we should do the same to make our job a breeze.

In software development, the technique that helps us with that is called refactoring and one definition is:

Discipline technique for restructuring an existing body of code, altering its internal structure without affecting its external behavior — Martin Fowler

In simple words, refactoring is all about changing the code but not what it does. If the code was doing A, after the refactor should still be doing A, not A.1 not A + B, just A.

If we end up breaking something during refactoring, then it isn't a refactor; it's a rewrite of code. The same goes when we start including features that we never were included initially.

The objective is to make the code maintainable and extensible. We do it by simplifying the code; when the code is simple, it's easy to read, contributing to understanding it better. This is key in reducing technical costs because by working with simple and clean code, we face less resistance to changes accelerating the software development process.

Through refactoring, we make the developer's life easier; while the customers are unaware of the changes, they kept seeing the same product.

There is a downside, though. Because we are changing how the code is written, how it looks, and how it feels to works with it. There are many instances to screw it up in an epic way. However, the risks are proportional to the size of the refactor, so we should always aim to keep the changes as minimal as possible. One rule that supports this idea it's the boy scout rule.

🏕️ Boy Scout rule

Leave the campground cleaner than you found it

Whether you're working on an important feature or a critical bug, if you spot something that can be improved, do it.

With this in mind, refactors will be tiny enough to not represent a significant risk.

What then when I discover that we need a massive change? Do I pause my current task and start the tedious big refactor?

- Absolutely not

Big changes are consequences of bad decisions and require a ton of effort. It's more usual to face this kind of monster while trying to improve legacy code. In this case, notify the team, evaluate the impact and treat it like any other feature. Treat big refactors as the exception to the rule; in general, we should avoid scheduling refactors because we run the risk of never doing them.

If there is a chance to tackle the problem one little refactor at a time, do this instead.

You can think of refactoring as gardening, a set of essential and frequent activities to have a beautiful garden. Like with plants, we have to maintain our code.

✅ Benefits of refactoring

- It helps to simplify the code, making it flexible, easy to understand and to work with it

- It helps to keep the project updated with new technologies and standards

- It reduces waste by allowing us to delete unnecessary and over-complicated code

- It helps to keep the big picture of the project. By refactoring often different pieces of code, we refresh the idea of how those parts work

🏆 The outcome of refactoring

Even when there isn't an ultimate form of our code because it's in constant change, we should always strive to have a clean code as an outcome. Although this cannot always be achieved, which makes good code an acceptable viable option.

The difference between both is that the clean code is the end state of the code in a given moment; when you read it, you can't find a way to make it better in that specific moment. Whereas with good code, we acknowledge that it has improvements, but we could keep polish it.

Depending on our time availability, we can choose to keep a good code rather than seeking to improve it; those changes can be delayed without causing any harm to the team.

Seek progress, not perfection

Refactoring is the never-ending pursuit of having a clean project.

When we should refactor?

There are many reasons to get back to read old code and refactor it, but without a clear purpose, we could end rebuilding things, falling into premature optimization, violations of the YAGNI principle, or adding new functionalities.

Don't refactor if you don't have a clear purpose in mind

Refactoring is a means to an end, so we need valid reasons to justify doing it, and "I don't like Pete's code" is not a valid reason.

A powerful reason is to simplify the code because it has become an obstacle to work with, or the team has gained a deeper understanding of the domain and the tools being used that can help to reduce the complexity.

Other valid and more specific reasons are:

- Preparing the code for incoming breaking changes on third-party dependencies

- Improving extensibility to facilitate new integrations

- Reveal the intent of obscure pieces of code to identify security issues easily

- Remove clear violations to good practices

The best time to consider refactoring is before adding any updates or new features to the existing code. In those situations, it's good to return and read the code to evaluate if it's in good shape to use it as a base for the incoming changes.

Not having a clear purpose doesn't mean we can forget about refactoring. On the contrary, we should always keep looking for what to improve, trying to find that purpose.

Considerations before refactoring

How can we improve something that we don't know it's wrong?

To refactor code, we first have to build knowledge about good practices, principles, and techniques that can help us to write better code. That way, we'll have the tools to identify bad code and know how to improve it.

Refactoring can be a high-risk discipline due to changing the code and preserving the current behavior, but with control version tools and automated tests, it becomes a less risky operation. Although, there are still things we should be aware of before starting refactoring code.

- Never refactor without automated tests. If you don't have tests, you lack the feedback to know if you broke something during the process. So abort the refactor and start writing those tests!

- Never add functionality. As devs, we can be tempted to use the opportunity to add new functionality, but by doing so, we could be introducing undetectable errors.

- Set limits to refactors to a file, module, class, etc.

- Always work at baby steps . You get early feedback, it's easier to start over, reducing the chances of wasting time.

- Back up every successful refactor using your control version tool once your tests are green.

The key is to have automated tests; that's the best way to ensure we are changing the code and preserving the behavior simultaneously.

Final thoughts

Refactoring is not an optional task. It's a matter of professional survival. If something hurts now, tomorrow it will hurt more, so pay special attention to the signs.

Develop the knowledge required to identify what is needed to do and trust your tests.

Embrace continuous refactoring to reduce the high risks of dealing with large refactors.

Do it often, with a clear purpose in mind, and focus on progress, not perfection.

Further reading

Fowler, M. (2018). Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code (2nd Edition) (Addison-Wesley Signature Series (Fowler)) (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional.

Here is an excellent article from Tiger Abrodi about the learnings of the above book

Martin, R. C. (2008). Chapter 1: Clean Code. In Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship (1st ed., pp. 1–15). Pearson.

Beck, K. (2002). Chapter 31: Refactoring. In Test-Driven Development: By Example (1st ed., pp. 181–191). Addison-Wesley Professional.

Feathers, M. (2004). Chapter 1: Changing Software. In Working Effectively with Legacy Code (1st ed., pp. 3–8). Pearson.